Penn State has been selected by the Department of Defense (DoD) as a partner for two of the

Administrator

Perovskites, a family of materials with unique electric properties, show promise for use in a variety fields, including next-generation solar cells. A Penn State-led team of scientists created a new process to fabricate large perovskite devices that is more cost- and time-effective than previously possible and that they said may accelerate future materials discovery.

Perovskites, a family of materials with unique electric properties, show promise for use in a variety fields, including next-generation solar cells. A Penn State-led team of scientists created a new process to fabricate large perovskite devices that is more cost- and time-effective than previously possible and that they said may accelerate future materials discovery.

“This method we developed allows us to easily create very large bulk samples within several minutes, rather than days or weeks using traditional methods,” said Luyao Zheng, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Materials Science at Penn State and lead author on the study. “And our materials are high quality — their properties can compete with single-crystal perovskites.”

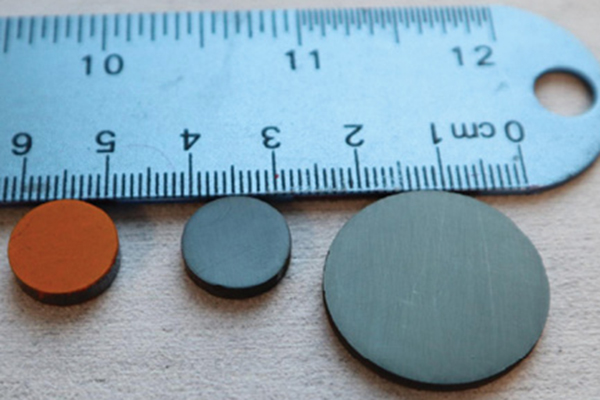

The researchers used a sintering method called the electrical and mechanical field-assisted sintering technique (EM-FAST) to create the devices. Sintering is a commonly used process to compress fine powders into a solid mass of material using heat and pressure.

A typical process for making perovskites involves wet chemistry — the materials are liquefied in a solvent solution and then solidified into thin films. These materials have excellent properties, but the approach is expensive and inefficient for creating large perovskites and the solvents used may be toxic, the scientists said.

“Our technique is the best of both worlds,” said Bed Poudel, a research professor at Penn State and a co-author. “We get single-crystal-like properties, and we don’t have to worry about size limitations or any contamination or yield of toxic materials.”

Because it uses dry materials, the EM-FAST technique opens the door to include new dopants, ingredients added to tailor device properties, that are not compatible with the wet chemistry used to make thin films, potentially accelerating the discovery of new materials, the scientists said.

“This opens up possibilities to design and develop new classes of materials, including better thermoelectric and solar materials, as well as X- and Y-ray detectors,” said Amin Nozariasbmarz, assistant research professor at Penn State and a co-author. “Some of the applications are things we already know, but because this is a new technique to make new halide perovskite materials with controlled properties, structures, and compositions, maybe there is room in the future for new breakthroughs to come from that.”

In addition, the new process allows for layered materials — one powder underneath another — to create designer compositions. In the future, manufacturers could design specific devices and then directly print them from dry powders, the scientists said.

EM-FAST, also known as spark plasma sintering, involves applying electric current and pressure to powders to create new materials. The process has a 100% yield — all the raw ingredients go into the final device, as opposed to 20 to 30% in solution-based processing.

The technique produced perovskite materials at .2 inch per minute, allowing scientists to quickly create large devices that maintained high performance in laboratory tests. The team reported their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

Penn State scientists have long used EM-FAST to create thermoelectric devices. This work represents the first attempt to create perovskite materials with the technique, the scientists said.

“Because of the background we have, we were talking and thought we could change some parameters and try this with perovskites,” Nozariasbmarz said. “And it just opened a door to a new world. This paper is a link to that door — to new materials and new properties.”

Written by Matthew Carroll for FOCUS on MATERIALS, Spring 2024.

Award keeps the Roys' legacy of interdisciplinary innovation alive

Two of Penn State's most impactful materials researchers were a married couple: the late Rustum and Della Roy. Their collaborative efforts and individual achievements have played a pivotal role in advancing materials science, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations, and inspiring future generations of scientists. Part of this inspiration is an annual award that helps shape the future of materials research at Penn State.

The Rustum and Della Roy Innovation in Materials Research Award is presented by the Materials Research Institute (MRI) and recognizes recent interdisciplinary materials research at Penn State that yields innovative and unexpected results. The award covers a wide range of research with societal impact and includes three categories: Early Career Faculty, Non-Tenure Faculty, and Research Staff, and Graduate Student. It exists thanks to a gift from Della and Rustum.

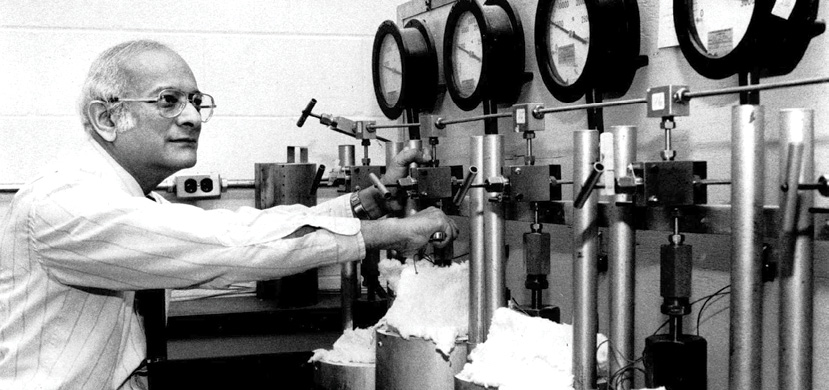

Della and Rustum were alumni of Penn State’s College of Earth and Mineral Sciences and were long-serving faculty in the college. Rustum served for more than 50 years as an Evan Pugh Professor of the Solid State, professor of geochemistry, and professor of science, technology, and society. He gained a global reputation as a pioneer in interdisciplinary research. This included the nation’s first Graduate Interdisciplinary Degree Program in Solid State Technology (now known as materials research), the first independent interdisciplinary Materials Research Laboratory (later became the Materials Research Institute), and the first undergraduate program in Science, Technology, and Society. He also founded two major national societies in these fields of research, including the Materials Research Society.

“He was always full of new ideas, new approaches, and most importantly he was a diehard optimist,” said Dinesh Agrawal, professor emeritus who worked with the Roys. “His eternal message was: Think positive, be persistent in your pursuit and you will attain success. He would always find something good or positive out of a hopeless situation or any seemingly failed experiment. He would always give you a sense of hope. Also, he was a workaholic, working almost 16 hours a day. His work-efficiency with alarming speed was amazing, he would be doing 10 things at the same time with quiet ease; even a man of 40 years old would not do that much work in one day what he was doing even when he was 85.”

Part of Rustum’s legacy is how effective interdisciplinary research has become at Penn State. In December 2019, a research team led by Steve Brint of the University of California, Riverside published an article in The Journal of Higher Education that evaluated the effectiveness of interdisciplinary research and cluster hiring at 20 universities; the study revealed that despite recruiting top experts in the field, interdisciplinary research was having difficulty taking hold. The study noted that “There are exceptions to this rule. One university in our sample stood out," which was Penn State.

Part of Rustum’s legacy is how effective interdisciplinary research has become at Penn State. In December 2019, a research team led by Steve Brint of the University of California, Riverside published an article in The Journal of Higher Education that evaluated the effectiveness of interdisciplinary research and cluster hiring at 20 universities; the study revealed that despite recruiting top experts in the field, interdisciplinary research was having difficulty taking hold. The study noted that “There are exceptions to this rule. One university in our sample stood out," which was Penn State.

During his graduate work, Rustum met Della as they shared an office and lab. Their relationship grew and they married in June 1948, a marriage that spanned 62 years until Rustum’s death in 2010. She became renowned as a leader in the world of cement and concrete, known for her work in advanced concrete materials for pavements, chemically bonded cements, ancient cement-based building materials, and high-temperature cements for geothermal wells. Della proved to be an inspiration to female scientists, as her work resulted in a series of pioneering moments for women in STEM. The mineral dellaite was named after her in 1965. She is one of only 112 women to have a mineral named after them as of May 2019. In 1987, she became the first female materials scientist and the first Penn State woman to be inducted into the National Academy of Engineering (NAE). She was the third female scientist overall, and with Rustum’s induction into the NAE in 1973, she formed the first spousal couple to be so honored. In 1971, with Penn State colleague Kathleen Mourant, she founded the journal Cement and Concrete, the first in its field, and served as its editor until 2005. Her other firsts included being elected to the World Academy of Ceramics as its first female member.

“I was a student at the Materials Research Laboratory (MRL) where Rustum and Della were faculty members,” said Michael Lanagan, professor of engineering science and mechanics. “They were part of a faculty team that created an amazing environment for students. The MRL was a unique place where there were shared labs, dedicated staff, and an international community that supported creative research.”

The winners of the Roy Awards, the individuals at Penn State carrying on this legacy of interdisciplinary research success, are announced at the annual Materials Day, which is the Materials Research Institute’s annual marquee event celebrating the best in materials research at Penn State.

This article appeared in FOCUS on MATERIALS , Spring 2023.

One of the more innovative energy-saving tools at Penn State was not implemented by a faculty member, employee, or graduate student. Instead, it was developed by undergraduate students who are part of an innovative and unique research fellowship offered by the Materials Research Institute (MRI).

MRI’s Undergraduate Research Fellowship is unique in that it offers undergraduate students an opportunity to receive training and use the high-end scientific instrumentation available in the Millennium Science Complex. This is something only students at a graduate level usually have access to. Each of the undergraduate fellows are assigned a few main projects for their time working with MRI faculty and research staff, and this included the innovative energy-saving idea, which was a sensor for laboratory fume hoods to make sure the fume hood sash was closed when not in use.

However, the fellowship experience is not limited to their assigned projects. They are exposed to various research projects that enable them to receive hands-on experiential learning working with research staff in MRI’s core facilities. And beyond this, they also receive opportunities to work with some of the approximately 1,000 researchers from 45 Penn State departments doing cutting-edge research work at the University. They also have opportunities to interact with MRI’s more than 100 external research partners from other higher education institutions and industry, giving them valuable contacts and resume points for future employment and graduate school searches.

The fellowship is the brainchild of its director, Maxwell Wetherington, assistant research professor, molecular spectroscopy. Wetherington was inspired to create the program after recalling his own Penn State student experience, which included earning a bachelor of science degree in engineering science, a master of science degree in material science and engineering, and a doctor of philosophy degree in materials science and engineering.

“I help support this capability, including learning how to operate the microscopes and troubleshoot them, which is important because it takes some time to learn all the machines’ quirks and how to mitigate them for the remote users,” Misra said. “Perhaps most importantly, I’ve learned when to know I can’t solve something, and more advanced maintenance is needed.”

Each year, five undergraduate students are selected as fellows. For the 2022-2023 version of the program that ended in May 2023, the students included Muhammad Ishak, third-year materials science and engineering; Harshit Jain, third-year computer science; Jongkyeong Kim, third-year year materials science and engineering; Baaz Misra, second-year computer science and engineering; and Alejandro Toro, third-year material science and engineering.

Kim’s work during his fellowship included the fume hood sensor. He was inspired by some of his sustainability coursework that taught him that fume hoods have some of the greatest impact on energy use in a lab. This is due to the amount of energy required to keep a consistent airflow to remove hazardous fumes in a lab. Closing the sash when the lab is not in use reduces the volume of air that needs to be treated and exhausted, thus saving energy.

Ishak’s project enabled him to work with a faculty member outside of Penn State, Tom Mallouk, currently the chair of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania. Like Kim, his project had an immediate impact on research at Penn State.

"I worked together with Mallouk to improve the accuracy and reproducibility of our Helium pycnometer, which measures the density and mass of solids, to develop a new, standardized operating procedure for that instrument,” Ishak said.

For Jain, his projects put into practice what he has learned as a computer science major, especially around machine learning and artificial intelligence. One was developing an innovative web application that allows a researcher anywhere in the United States to find a specific research instrument near their location.

The other computer science-focused Fellow, Misra, credits the program in part with his switching to his current major from electrical engineering. Misra’s project work included supporting remote transmission electron microscopy, which involves users outside of University Park logging into a system that enables them to control the microscopes remotely.

Toro also worked with remote users at Penn State Harrisburg on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and related focused ion beam work, along with prepping samples to be

characterized by these tools.

“Right now, professors at Harrisburg are able to commission projects and research to be done on the SEM microscopes and focused ion beam for their own research,” Toro said. “Through the fellowship, I can save these researchers time and money since they can do this work on our instruments remotely, so they do not have to travel to University Park from Harrisburg.”

For more information on the program and to learn more about industry sponsorships, contact Wetherington at mtw5027@psu.edu or David Fecko, director of MRI industry collaboration, at dlf5023@psu.edu.

This article appeared in FOCUS on MATERIALS , Spring 2023.

Six Penn State materials researchers have received the 2023 Rustum and Della Roy Innovation in Materials Research Award, covering a wide range of research with societal impact. The award is presented by the Materials Research Institute (MRI) and recognizes recent interdisciplinary materials research at Penn State that yields innovative and unexpected results.

Moore's Law, a fundamental scaling principle for electronic devices, forecasts that the number of transistors on a chip will double every two years, ensuring more computing power — but a limit exists.

The National Academy of Inventors (NAI) named Qiming Zhang, distinguished professor of electrical engineering in Penn State’s College of Engineering, a fellow — the highest professional distinction awarded to academic inventors.

Silicon has long reigned as the material of choice for the microchips that power everything in the digital age, from AI to military drones — so much so that “silicon” is almost a synonym for tech itself.

The scientific community has long been enamored of the potential for soft bioelectronic devices, but has faced hurdles in identifying materials that are biocompatible and have all of the necessary characteristics to operate effectively. Researchers have now taken a step in the right direction, modifying an existing biocompatible material so that it conducts electricity efficiently in wet environments and can send and receive ionic signals from biological media.